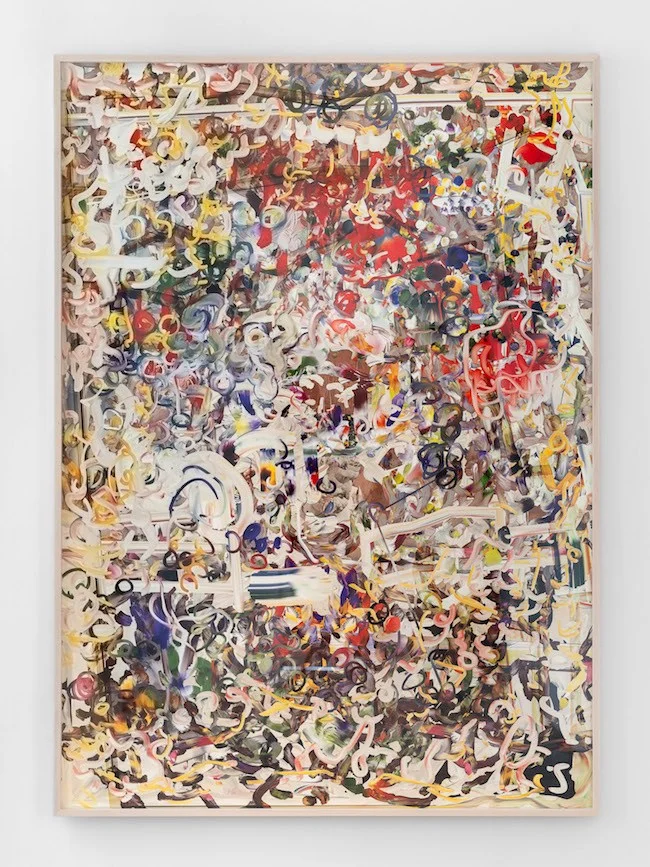

Petra Cortright, man_bulbGRDNopenz@CharlezSchwaabSto9ds (2016).

Digital painting on Sunset Hot Press Rag paper, 82.4 x 59 inches. Image courtesy of 1301PE, Los Angeles. Photo: Chris Adler.

Petra Cortright at 1301PE

Post-internet darling Petra Cortright first found artworld attention in the mid-aughts with intentionally basic webcam video self-portraits—prescient ripples of the internet’s impending selfie tsunami. As Cortright has shifted her work to be more commercially friendly, her work has spent more time digitally dwelling on the medium of painting. Since all of her work is at its essence a digital file, Cortright has the possibility of any printable material becoming her canvas. Thus an infinite amount of “unique” printed and digital works can all spring from one mother file, disrupting the notion of the singular art object.

Mining the vernacular internet of sites such as Pinterest for source material, Cortright quotes crowd pleasing art historical hits—from vaguely surrealist-looking interiors to explosions of patternistic abstraction à la Klimt. For her printed works, the medium for all is “digital painting,” a curious descriptor for pieces whose material process has more in common with printing or the seriality of photography, than with paint on canvas. Look closely at what appears to be the sensuous curve of a brushstroke and you will see the familiar, jagged edge of rasterized pixels. Cortright is clearly adept at her digital tools and rides the edge of pictorial skeuomorphism skillfully.

This edge is lost in the four flash animation works also on view, endless loops of animals cavorting through artistically vandalized landscapes. While their intention may be to riff on the screensaver, they never transcend their medium. The true gem of the show is bollywood stars nude_creatine Pyruvate (2017), an 11 minute video of Cortright’s Photoshop processes in subtle slow motion. The effect is mesmerizing, providing motion and mobility to what is a traditionally static object while also being a beguiling expression of aesthetics as data. While it is clear Cortright has a firm grasp of the possibilities of her medium, the serializing of her works as large scale canvas prints that riff on art history feels less than convincing. Certainly now may be the moment to use digital tools to consider the past and future of painting, but there is a sincerity lacking in many of the works included; they feel too indulgently digestible or smirkingly one-note to truly satisfy.

Jean-Pascal Flavien, statement house (temporary title) protocol Los Angeles (2016). Various materials, 8.5 x 16.5 x 16.5 feet. Image courtesy of the artists and Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Jean-Pascal Flavien & Mika Tajima at Kayne Griffin Corcoran

It seems fitting that Los Angeles born Mika Tajima’s first show in her hometown includes one of her candy-colored Jacuzzi paintings. What could be more quintessentially L.A. than a sunset-ombré hot tub, its slick sexy object-ness epitomizing the glamor of Hollywood. Her co-exhibitor Jean-Pascal Flavien likewise embraces the city’s marquee industry with statement house (temporary title) Los Angeles (2016), a diminutive baby pink house—sited in the gallery’s lush courtyard—to be occupied intermittently by two screenwriters over the run of the show. Both artists are preoccupied with people: how we work, how we live, how we communicate, and the way in which the objects and environments that surround us define and manipulate our interactions.

Office furniture has been a source of inspiration for Tajima for some time. In 2011 she made sculptures repurposing an original 1970s Herman Miller Action Office system, the first office “cubicle”. She also has an ongoing series, Furniture Art (a reference to Erik Satie’s Furniture Music [Musique d’ameublement], 1917), a series of infinitely repetitive compositions meant to blend into the background like aural decor. As much as she enjoys the formal possibilities of the everyday office’s visual vocabulary, Tajima’s interest also lies in the role of the workplace itself as a site of production and performance. A number of textile works are included in the show from Tajima’s Negative Entropy series (2015-16): a set of Jacquard-woven “acoustic portraits” of workers recorded in their factories and offices which are then abstracted into patterns for the looms. The end result is as painterly as a Rothko while still distinctly digital in a lo-fi, ’80s sort of way (Jacquard looms are early precursors to modern computers). Here too Tajima fortifies her sensual objects with a consideration of the intricacies of production and labor.

In opposition to the many-pronged manifestations of Tajima’s output, Jean-Pascal Flavien’s contribution to the exhibition is singular to the point of being monolithic. A single form—the shape taken from the footprint of the built house in the courtyard—is repeated in cutout aluminum sheets hung throughout the main gallery. The intention of the house is to exist as a framework for language, an empty box to be filled with the potential possibility for engagement. As with previous iterations of his house projects, Flavien invites collaborators to inhabit the space, creating texts to compliment and complete the work. For this particular version two screenwriters have occupied the bungalow, composing Tweets that script its daily activities throughout the run of the show.

A perusal of their respective Twitter feeds finds them both funnier and less myopic than I expected from such an intellectually staged feedback loop. This proved to be the saving grace for a project that could have easily read as real-estate-as-performance. Market forces and speculations are briefly addressed in a few early Tweets, but given the current heated conversation on the role of galleries and artists in gentrification, it seems remiss that such issues are mostly ignored. In his formal, repetitive simplicity Flavien attempts to make physical the endlessly possible scenarios of a space. But this openness, inactivated, can start to look more like emptiness.

The lynchpin for social practice artwork always lies in collaboration, or how well the participants engage with one another. There is an ever-present danger of the work being swallowed by its own intentions, either closing in on itself or opening into gross spectacle. It is clear that both artists are good collaborators, Tajima with the fabricators, translators, and operators that make her objects possible, Flavien with his activating inhabitants. It’s also interesting to find so many objects in a show so preoccupied with interaction. What the objects themselves communicate is harder to quantify. Tajima’s almost archivist eye towards industrial design translates easily into covetable luxury objects. But her works also carry within themselves a consideration of their humanity, however artfully abstracted. Flavien’s plans for utopian environments of possibility can seem more like souvenirs on display next to the tourist attraction, shorthand symbols for an idealized experience that might never have happened at all.

http://contemporaryartreview.la/jean-pascal-flavien-mika-tajima-at-kayne-griffin-corcoran/

On the Verge of an Image: Considering Marjorie Keller.

A LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division) exhibition, the Gamble House, Pasadena, CA (2016).

Photo: Jeff McLane.

On the Verge of an Image: Considering Marjorie Keller by LAND at the Gamble House

Tucked away amongst the lush, palatial estates of Pasadena is the historic Gamble House, a lovingly preserved arts and crafts mansion built in 1908. For the next two months the Gamble House, in conjunction with the itinerant Los Angeles Nomadic Division, plays host to an ambitious and thoughtful exhibition curated by Alika Cooper and Anna Mayer exploring the work and influence of avant-garde filmmaker Marjorie Keller.

In a too-brief career spanning roughly 1972-1991 Keller made 25 films in a lyrical, diaristic, and non-linear style that often incorporated footage from her own life, family and experiences. Keller was a committed feminist who nevertheless had concerns about the stringent requirements of feminist theory. The curators appear to have taken this to heart, assembling a diverse array of works that examine femininity and the body using an array tactics of representation—from Chantal Akerman’s interrogation of the male gaze in La Chambre (1972) to the delightfully optimistic Inquiring Nuns (1968) by Kartemquin Films. These works provide a textural contrast to the four films by Keller included in the exhibition, studded throughout the home like easter eggs. Tucked inside the linen closet is Keller’sDaughters of Chaos (1980), a meditation on female sexuality and aging that acts as the exhibition’s heart, brimming with sentimentality without crossing the line into sappiness.

Other highlights include a series of photographs by Paul Pescador 9/6 (01-12) (2016). Shot on location using objects found in the house, these works create playfully absurd visual moments, which bring a human animation to the museum-like seriousness of the space. Naomi Fisher’s sculpture, Dancarchy – Rugrosa Rose (2016), similarly incorporates some of the house’s distinct visual flourishes into cast wax panels that will weather on the veranda for the run of the show—a natural aging process that points to the constant fight against entropy of the house itself. The ease with which the works slip into their domestic environment underlies the universality of the themes that Keller and the exhibition’s curators both attempt to explore, transcending time and exposing a broader audience to the work of an under-appreciated artistic maverick.

On the Verge of an Image: Considering Marjorie Keller runs October 8-December 11, 2016 and is presented by Los Angeles Nomadic Division at The Gamble House: University of Southern California, School of Architecture: 4 Westmoreland Place, Pasadena, CA 91103.

Arden Surdam, Solid Liquid (2016) (installation view). Glass Vitrines, Agar Agar, Paper, Squid, Octopus, Eggs, Cyanotype, Tanzanite Blue Photo Oil, Coffee, Beeswax, Olive Oil. The Situation Room. Image courtesy of the artist

Arden Surdam at The Situation Room

Arden Surdam is a photographer by training, but since beginning grad school at CalArts in 2013 she’s mostly been cooking. Surdam’s most recent experiments with food and photography are currently on view at The Situation Room, a renovated garage nestled in an artfully landscaped backyard in Glassell Park. The checklist reads like a cook book: Baby Octopus, Cyanotype, Olive Oil. Instead of tossing her ingredients in a frying pan, Surdam puts them on a sheet of photo paper and leaves them outside to rot. As the food decomposes, it reacts with the photo chemicals to create an image. The result is surprisingly painterly and evokes what one might expect to see under a microscope: blooming whorls of biomorphic shapes on shifting aquatic waves.

Presented in the exhibition in backlit open air vitrines covered in a thick layer of agar, the effect isnuminous—artifacts on glowing altars, miraculous images conjured from mundane materials. While the majority of the foodstuffs have been removed, some organic matter still remains, decomposing over time and likely to present a distinct odor to those visiting during the final days of the show.

The images themselves will also degrade during this process, flouting the art historical narrative of the everlasting art object. Instead, they are content to live out their natural role in the circle of life—just like the cup of yogurt in your fridge. This fleeting moment, captured, adds an additional poignancy to Surdam’s project. In an art world that can sometimes feel dominated by mega-galleries, privately financed vanity museums, and the proliferation of commerce-on-steroids art fairs, this embrace of an art object’s potential for ephemerality is gratifying.

Arden Surdam: Solid Liquid runs September 8-September 30, 2016 at The Situation Room (2313 Norwalk Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90041)

http://contemporaryartreview.la/arden-surdam-at-the-situation-room/

Eleanor Antin, Georgia de Meir (1969). Table, chairs, dominoes, sweater, bowl, California grapes. Image courtesy of the artist and Diane Rosenstein, Los Angeles.

Eleanor Antin at Diane Rosenstein

You are what you buy. As a child of the ‘80s this understanding has been programmed into me since the commercial breaks of Saturday morning cartoons. 20 years before I ever set eyes on an American Girl catalog, Eleanor Antin was already acutely aware of the abilities of material possessions to tell the story of an individual.

Previously a painter before moving on to assemblage, Antin had already begun her career-long exploration of identity with her first conceptual project, Blood of a Poet Box (1965-1968), by gathering blood samples from poet friends and storing them on glass slides. Then in 1968, Antin traded the retailWunderkammer of New York City for a sleepy beach town outside of San Diego. Shortly thereafter, she found her Rosetta Stone in the Sears catalog. This bible, of sorts, contained a vast array of consumer goods, making it the perfect palette for Antin’s method of matching material objects to personhood. “The Sears catalogue was especially crowded with objects from lowly brush shavers to corsets, from ladders to wedding gowns,” she explains in the introductory text for the exhibition. The series of portraits, created from various catalogues, became two exhibitions: CALIFORNIA LIVES (1969) andPortraits of Eight New York Women (1970). The combined work from both was on view recently as a single exhibition, What Time is It?, at Diane Rosenstein Gallery.

Shopping as portraiture makes a handy form of identity abstraction—most people need a table or a pair of shoes at least—and in the high-consumerist world taking shape post WWII, the possibilities for interpretation were infinitely multiplied. The assemblages from CALIFORNIA LIVES in particular are not flashy, but rather clusters of quotidian materials arranged nonchalantly in the gallery. Howard(1969) consists of a pair of dress shoes, with a pair of rolled up socks and a watch tucked inside. The Murfins (1969), where a partially completed brick wall stands behind a ladder on which rests a forgotten can of Fresca, conjures a scene in which the subjects have stepped away for a quick break and will return any moment to take up where they left off.

This economy of materials does not diminish the power of the personal narratives that Antin depicts. Each detail contains a clue; from the saucy, pink-lipstick-stained cigarette in Jeanie (1969), to the depressingly insufficient fruit tray that accompanies soldier Tim (1969) off to war. To aid the viewer in unraveling her subjects, Antin provides brief character texts about each (and the occasional footnote scrawled on the wall in pencil).

These briefs are installed in a single room in the gallery along with the noisiest of her works, Molly Barnes (1969). Miss Barnes seems to have neglected to turn off her electric razor following a kerfuffle in which she spilled her pills and powder. The vibrating razor rests on a delicately soiled pink bath mat, its insistent buzzing audible to the viewer throughout the show.

After CALIFORNIA LIVES was poorly received upon its debut in New York, Antin doubled down on her methods but altered her subjects, creating Portraits of Eight New York Women (1970), each inspired by a prominent female member of New York’s avant-garde community. Reflecting the often performative lives of these women, the arrangements become more dramatic in this body of work. There is the show-stopping Carolee Schneemann (1970): a dramatic sweep of red velvet is personified and preening in front of a mirror, yet is still grounded by the earthy jar of honey at its feet. The work is haunting and elegant. Meanwhile, a more playful Yvonne Rainer (1970) balances a heaping basket of flowers atop her Exercycle, her sweatshirt lingering on the edge of the seat. And what exactly does Hannah Weiner(1970) plan to do with that hammer? The tool rests threateningly amongst an otherwise saccharine picnic arrangement complete with gingham-clad, heart-shaped chairs.

Here too, the issues of subjectivity and identity bubble up to the surface. One work, the portrait ofRochelle Owens (1970) was deemed inaccurate by its subject; in its place, a wall label reads “ROCHELLE OWENS REMOVED / PIECE DID NOT LIVE UP TO SUBJECT.” According to the text accompanying the exhibition, only one woman wanted her portrait after the show. But, after a year ”she called to say the piece was making her nervous and her therapist suggested that she give it back.”

These are portraits that both celebrate and scrutinize their subjects. Antin does good work digging into the complexity of people’s (and particularly women’s) identities and relaying those specific details with simple goods considerately placed. The sculptures resonate by capturing the imperfections and nuances that people project into the world, encompassing style, poise, and presence, yet also a darker internal turmoil that many of us contain under the surface. Her portraits celebrate and expose the complexities of each of our inner lives, while also unmasking a dependence on capitalist structures to express the self. These objects become stand-ins for the body, infused with the energy of life, as well as the pathos of mortality.

Eleanor Antin: “What time is it?” runs from May 14 – June 18, 2016 at Diane Rosenstein (831 Highland Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/eleanor-antin-at-diane-rosenstein/

Tanya Aguiñiga, Teetering of the Marginal series (all 2016). Photo courtesy of the artist and the Landing. Image: Joshua White/JW Pictures.

3 Women at The Landing

In her essay “How to Install Art as a Feminist” Helen Molesworth critiques the oedipal narratives of traditional art history, and proposes instead a looser network modelled on the rhizome. Disparate art-historical nodes are here connected via “elective mothers”; artistic influence is mapped across time and space. 3 Women at The Landing brings together the work of two developing artists in conversation with an iconoclastic voice from the past—illuminating the powerful possibilities of such methods of curatorial inquiry.

The grande dame in 3 Women is Leonore Tawney, a student of Moholy-Nagy and maverick textile pioneer. Her precise line drawings bring to mind the work of her close friend Agnes Martin. But it is her monumental linen works that best illustrate her innovative techniques. Tawney freed tapestry from the wall to float in space, transforming flat planes into dramatic, figurative volumes. Spirit River (1966) in particular transfixes with nuanced color shifts from inky blue to black; a night sky reflected in the ripples of thread-made-water.

The paintings of Loie Hollowell likewise find their power in the interplay of line and texture.They often seem to vibrate along the sinuous swaths of rough and slick paint that twine through her compositions like intestines. Like Hollowell, Tanya Aguiniga’s works are equally bodily, but far less muscular. In the back of the gallery flesh-hued forms hang from the ceiling, cradled in improvised macrame slings. These works make use of the corporal, organic forms of fiber pioneered by Tawney but rather than austere, monolithic figures Aguiniga gives us fragile, misshapen mutants. Freed from the false binary of the heroic individual or obliterating community the triangle of 3 Women gives space to a more nuanced conversation, one which allows a far healthier balance of individuality and interdependence.

3 Women runs July 23-September 17, 2016 at the Landing (5118 W. Jefferson Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90016)

Bright Maing Melchi Puleo (2016). Installation view. Image courtesy of the artists and Ochi Projects.

Bright Maing Melchi Puleo at Ochi Projects

The art world is a social place; overlapping community circles and spheres of influence define the shape of the narratives that eventually make their way into the annals of history books. Bright, Maing, Melchi, Puleo, a four person group show currently on view at Ochi Projects, makes material this art world truism, allowing personal ties to constitute the conceptual framework of the show. Jacob Melchi and Antonio Puleo, friendly colleagues with like-minded work, used the opportunity of their show to each invite another artist, Sara Bright and Susanna Maing, respectively, into a four-way conversation about painting and mark-making.

Each painter included in the exhibition works in a similar sphere of politely mannered abstraction, using disparate processes to come to homologous aesthetic ends. But even within this single genus there are many unique expressions. Bright’s energetic frescos and dynamically glazed ceramics play against Melchi’s firmer, more geometric line forms. Meanwhile Maing’s sinuous, organic shapes seem in a constant state of flux, while Puleo’s work is stable enough to materialize in duplicate outside of the canvas as a series of solid, carved-wood sculptures.

These meandering paths of difference loop back on each other, connecting and reconnecting the four separate bodies of work. There is a sameness in Melchi and Puleo’s formalness as much as there is a familiarity in Bright and Maing’s looser mark-making. Although it can often be the case with group shows based on a social mileu, the exhibition avoids becoming too hermetic or obscure to the viewer. This is helped by a roomy installation which openly engages with the gallery’s architecture, drawing the viewer into its world. Overall the feel is of a cozy slumber party, four friends swapping stories companionably in the moonlight.

Bright, Maing, Melchi, Puleo runs from May 14–June 18, 2016 at Ochi Projects (3301 W Washington Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90018).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/bright-maing-melchi-puleo-at-ochi-projects/

Julie Beaufils, installation view at Overduin and Co. (2016). Image courtesy of the artist and Overduin and Co.

Julie Beaufils at Overduin & Co.

The record store occupies a special place in the psychic space of those who revere physical media. In the age of e-everything, it is one of the few places (including art galleries) where the in-person experience still reigns supreme. Upon entering Julie Beaufil’s new solo show at Overduin and Co. you’ll notice that the paintings are hung unusually high. Below are a series of black wooden boxes filled with dozens of individually wrapped drawings displayed like LPs for the viewer’s perusal. Executed in a breezily simple linear style, these drawings depict witty, succinct one-liners about love, sex, and music.

In the second gallery a series of larger paintings whir with the velocity of a turntable’s centrifugal motion, or the brisk wind of a car on the freeway. Beaufil’s hazy brushstrokes and muted palette court a sense of nostalgia heightened by her depictions of ‘80s-specific hairstyles and an oversize cell phone. There is a feeling of zooming forward while simultaneously looking back, viewing the world through its reflection in a rearview mirror.

This concentration on an idealized past is a particularly Los Angeles state of mind. The stuff dreams are made of—sex, cars, and rock and roll—are mass-produced on backlots and studios from Hollywood to the Valley and peddled across the land in theaters and tabloids alike. In some ways this subject matter is low-hanging fruit, engineered to play to the emotion of longing for a halcyon time that likely never truly existed. As such Beaufils less-is-more sensibility can come off thin in her new paintings, especially when juxtaposed with the tight, self-contained packages of her drawings.

Julie Beaufils: In Tongues runs from May 15–June 11, 2016 at Overduin & Co. (6693 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90028).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/julie-beaufilsat-overduin-co/

Erin Jane Nelson, Little Master (2016). Inkjet on cotton, various fabrics, cotton batting, embroidered patches, pearls, charm, aluminum and FIMO clay, 52 x 49 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Honor Fraser.

default at Honor Fraser

What does the internet look like? A pile of photographs and half formed memes; “just another WordPress site;” so many cats. A particular corner—adjacent to the one defined by Hyperallergic as The Teen Girl Tumblr Aesthetic—looks a lot like the quilts of Erin Jane Nelson. Nelson prints found and original images on cotton which she layers along with charms, pearls, and beading into jumbled compositions that capture the eclectic chaos of a tumblog full of pet pictures and animated gifs.

Two of Nelson’s quilts are included in the video-heavy group exhibition default, currently on view at Honor Fraser. default proposes that pixels, and the software that enables their creation, are the readymades of the 21st century, updating the industrial revolution of Duchamp’s Fountain(1917) to today’s era of digital disruption. Also on view is Trisha Baga’s Competition/Competition (2012), a single-channel video installation which bridges the gap between object and pixel image. The piece combines a meditatively simple animation with an ordinary water bottle to sparkling optical effect. In the same room Victoria Fu’s beguiling Belle Captive II(2013) floats disembodied figures from stock images over rosy gradient dreamscapes.

Contemporary art shows that take the internet as their inspiration often gather together works that possess a particular digital aesthetic, which was dubbed “The New Aesthetic” by Bruce Sterling around 2012. The internet “look” features pixelated imagery, 3D rendering, and other hallmarks of computer generated content. Refreshingly, default’s focus on digital materials as readymades creates an entry point for a far more wide ranging consideration of the ways technology is shaping visual culture than strictly aesthetic shifts. This conversation is particularly important for the art gallery, a site that is predicated on IRL experiences with singular objects.

default runs from April 30–June 11, 2016 at Honor Fraser (2622 S La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90034).

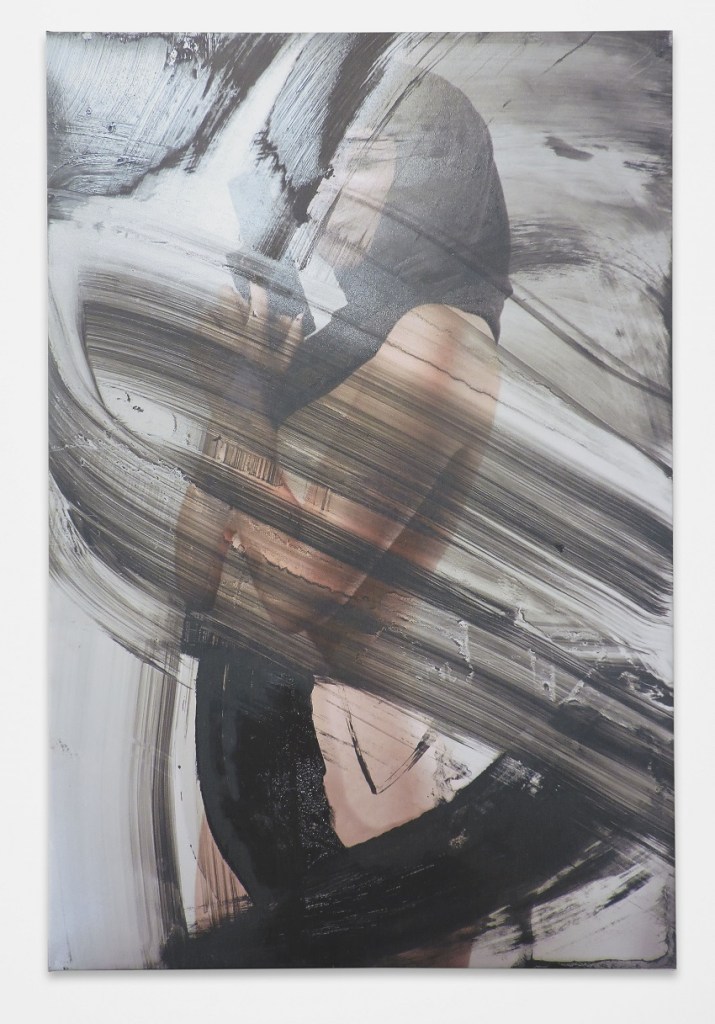

Rita Ackermann, JEZEBELS III (2015). Archival print on canvas, 59.5 x 39.75 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and FARAGO.

Rita Ackermann at FARAGO

The original Jezebel was a biblical queen notorious for convincing her husband to disavow the Hebrew god—and her eventual demise at the hands of her courtiers. Since the 20th century, the name is much more closely associated with “fallen women,” whose sexual appetites and seductive wiles lead otherwise “god-fearing” men astray. In her new series, Rita Ackermann explores this dark side of the madonna/whore continuum, of unapologetically powerful and sexual women, fully possessed and combat-ready.

Each of Ackermann’s three digital prints on canvas, currently on view at FARAGO, depict a nude woman, wearing only a hijab and brandishing a firearm. The images (shot by Richard Kern) have the distinct flavor of a fashion shoot. Staged before painted backgrounds, the resulting photos were then reworked repeatedly via photography, photocopying and painting before being printed onto canvas.

Women and war are both familiar subjects in Ackermann’s work. Her series of ballpoint pen works from the 90s depicted militaristic imagery including a portrait of the Unabomber. Although the headscarves and guns in these new works read easily as a politicized message in the age of ISIS, much more resonant are the strong assertions of female empowerment and self-possession. Through Ackermans’ seasoned and steady gaze these women inhabit an elevated plane, more soldier than Bond girl. Their nudity is alluring without diminishing the certainty that they are armed, dangerous and ready for a fight.

Rita Ackermann: JEZEBELS runs March 12-April 16, 2016 at FARAGO (224 W 8th Street, Los Angeles, CA 90014)

Photography class in Cabbage Patch (no date). Photo by Barbara Morgan. Image courtesy of Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, Asheville, NC.

Leap Before You Look at The Hammer

For a brief slice of history along the shore of North Carolina’s Lake Eden, there existed a utopian educational experiment called Black Mountain College. The Hammer’s new exhibition, Leap Before You Look, begins with a gallery dedicated to the school’s founding couple in art: Anni and Joseph Albers. The interplay between Joseph’s highly formal abstract paintings and Anni’s magnificent textiles are a fitting opening to the show’s deft exploration of the long-defunct College.

Cross-pollination was encouraged at Black Mountain; the juxtapositions within the exhibition of art with architecture, pedagogy, poetry, and music sing. A room devoted to the graphical scores of John Cage and the translations by his collaborator, pianist David Tudor, bleeds over into recordings of experimental poetry and dynamic photographs by Hazel Larson Archer of Merce Cunningham mid-dance. Elsewhere, textiles and ceramics are given equal weight to their pictorial brethren, in keeping with Black Mountain’s Bauhaus roots. Ruth Aswawa’s Untitled (S.272) (1955) a breathtaking, voluptuous wire sculpture holds its own next to Minutae(1954), Robert Rauschenberg’s brightly tropical first combine (made as a set piece for a school theater production).

The fact that the college was not an art school at all, but a liberal arts institution founded to include art at its core is worth noting. In a time when education, particularly in the arts, is so embattled, surely there are lessons to learn from this scrappy, innovative pedagogical experiment. The formidable legacy of the wide constellation of minds attracted to and nurtured by Black Mountain speaks to the immense creative and transformative potential in the fuzzy zones where disciplines overlap, and the power to be found in collaborative communities.

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 runs February 21–May 15, 2016 at The Hammer Museum (10899 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90024).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/leap-before-you-look-at-the-hammer/

Laure Prouvost, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek (2016). Installation (detail). Image courtesy of the artist and Fahrenheit. Photo: Deborah Farnault.

Laure Provost at Fahrenheit

There has been a disaster: a nuclear meltdown or some other man-made destructive event. Spilling across the floor a molten layer of blue resin captures eggshells, palm fronds and smashed electronic devices. Like the primordial ooze of the La Brea Tar pits entombing the detritus of our age for posterity—or just an archetypal L.A. swimming pool littered with debris after a high school rager—Laure Prouvost’s installation exemplifies the toxic post-apocalyptic possibilities of Los Angeles’s landscape.

Located in the center of the spill, an oasis of two bucket seats, shaded by wilting palms, awaits the viewer to recline while watching Lick in the Past(2016), Prouvost’s video meditation on adolescence and Los Angeles. As a European in the City of Angels, Prouvost is fascinated with Southern California car culture; the loose narrative thread of the work centers on a group of teenagers in a car as they hang out, cruise aimlessly, and talk about the adventures they hope to someday have.

The teens hopeful dialogue of longing and fantasy is intertwined with a viscous, sensual world of Prouvost’s making. Topics include raw eggs, squirting milk, and sea creatures, while intermingling visuals of udders, tentacles and slippery leeks cut in (all in Prouvost’s snappy, signature editing style). Sex and violence are repeatedly broached from the innocent sucking of tits to the more disturbing biting off the head of a bird. Actual footage of strangers performing these events flare up on screen; meanwhile the teens live out their wild fantasies with a safe caressing of the hard body of their vehicle and the licking their iPhones; a PG-13 counterpoint to the raw and surreal imagery of the interspersed cuts. Taken as a whole the installation reads as a love letter to the rawness and angst of our pubescent psyches as well as an ode to Los Angeles in all its toxic yet alluring glory.

Laure Prouvost: A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek runs from January 31–April 9, 2016 at Fahrenheit (2254 E. Washington Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90021).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/laure-provost-at-fahrenheit/

Akosua Adoma Owusu, Kwaku Ananse (film still) (2013). HD video, color, sound, 25 min. Image courtesy of the artist and Obibini Pictures.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Akosua Adoma Owusu at Art + Practice

Njideka Akunyili Crosby dwells in the domestic. There is a warmth to her show of new works at Art + Practice, like stepping into a long-familiar living room. Large scale works on paper depict the artist alongside family and friends in poses of comfort and repose. They look directly out of the picture frame with an irrepressible confidence: ‘beautyful’ and proud. As a woman and person of color these politics of representation are not lost on Akunyili Crosby, and it is to be celebrated that her thoughtful representations of non-white persons are currently on display not just in Leimert Park but also at the Hammer’s main building in Westwood.

Akunyili Crosby utilizes a process of Xerox transfer printing to build highly patterned grounds on which she overlays her painterly scenes and portraits. Combining an assortment of material from her personal life in the US, as well as from her homeland of Nigeria, she manipulates a largely Western technique to mimic the rhythms of traditional African textiles, expertly blurring the cultural divide asserted by colonialism.

Filmmaker Akosua Adoma Owusu also explores the politics of pattern in her short film Intermittent Delightwhich playfully interrogates gendered work and cultural appropriation with a mashup of textile patterns, action footage of weavers, and a cringingly retro refrigerator commercial. Also on view is the narrative Kwaku Ananse, a coming of age tale of an outcast teen in search of life purpose. This story is interwoven with the West African fable of Kwaku Ananse, the trickster spider. This celebration of Ghanian mythology also draws heavily from the filmmaker’s biography. In the film she explores the age-old quandary of mortality in lush visual detail. Taken together, the work of both artists provide thought-provoking contemporary statements as to the importance and impact of the often marginalized realms of pattern and decoration as well as the personal and domestic.

The Beautyful Ones and Two Films runs from September 12–November 21, 2015 at Art+Practice (4339 Leimert Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90008).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/njideka-akunyili-crosby-and-akosua-adoma-owusu-at-art-practice/

See Through at Elsie’s Watch & Repair (installation view). Image courtesy of Solar.

SEe Through at Elsie’s Watch and Jewelry Repair

Up the block from Jumbo’s Clown Room on Hollywood Boulevard, there is a special summer group show hiding amongst the jam-packed antiques and curiosities at Elsie’s Watch and Jewelry Repair. Organized by the newly formed Solar (Surrealists of the Los Angeles Region) the exhibition pits art against antiques in one big mashup of the weird, the shiny, and the meticulous.

In contrast to more common lo-fi exhibition venues (garages or apartments), the presentation of a contemporary sculpture exhibition within an antiques store is a welcome rejoinder. The context domesticates this group of modestly sized sculpture (a scale often lacking in sculptural exhibitions of late), allowing the medium an approachability that rivals that of wall-friendly painting.

The conceit of glass-enclosed artwork helps guide the viewer on a hunt to discover the works nestled throughout the store. Many of the pieces pay homage to their surrealist forebears, including Julio Panisello’s Julio’s Tea which serves a tea bag made of ‘100% Julio’s Hair’ a la Meret Oppenheim. Others, like Kim Tucker’s Self-Portrait: Saying Goodbye, embrace the freedom allowed by Surrealism’s dream-heavy underpinnings with singular weirdness. Solar’s embrace of the Surrealist ethos seems particularly apt in the golden age of zombie formalism, and the idiosyncratic nature of the works included is in turn heightened by the non-traditional exhibition venue.

See Through runs from August 1–31, 2015 at Elsie’s Watch and Jewelry Repair (5177 Hollywood Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90027)

http://contemporaryartreview.la/see-through-at-elsies-watch-and-jewelry-repair/

Tala Madani, Dirty Protest (2015). Oil on linen, 76 x 79 x 1 3/8 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery.

Tala Madani at David Kordansky

The titular smiley face is the motif in Tala Madani’s first solo show in Los Angeles, now on view at David Kordansky Gallery. The simplicity and naiveté of the symbol, with its genesis in hippie culture, are a good foil to the flat Eastern style and Freudian undertones of her paintings. In Madani’s world, exaggerated phalluses abound, human excrement is commonplace, and expressive yellow lines connote piss and saintly ecstasy—smartly conflating the two à la Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ. Many of the compositions mimic Christian iconography (mainly the Virgin and Child, and Christ’s crucifixion), but are presented scrambled, referencing S&M culture and scatology. Santa Claus also gets reimagined, depicted wielding Justin Timberlake’s “Dick in a Box” to mask indiscriminate urination.

Madani’s subjects are almost exclusively male and rendered in a painterly style that borrows heavily from comic books—a style most often associated with the hyper-masculinity that she skillfully mocks. Beyond the babies covering themselves in feces and young children with massive genitalia, her adult figures are infantilized, depicted bald and nude or clad solely in diaper-like loincloths. Above this filth, the smiley face reigns, mocking and masking Madani’s figures with inhuman persistent cheerfulness. Despite its grotesquerie, the show feels light and playful, studded with works that deliver a chortle of laughter even as they prey on our most immature and childish impulses.

Tala Madani: Smiley has no nose runs July 18 – August 29, 2015 at David Kordansky Gallery (5130 W Edgewood Place, Los Angeles, CA 90019)

http://contemporaryartreview.la/tala-madani-at-david-kordansky/

Olaf Breuning (2015) (installation view). Image courtesy the artist and Michael Benevento.

Olaf Breuning at Michael Benevento

In an art world that often takes itself too seriously, it’s refreshing to discover an artist who approaches life with humor and joy. Olaf Breuning takes this tact with his self-titled exhibition now on view at Michael Benevento.

Dominating the main gallery is a series ocular Photoshopped collages adhered to the wall as large vinyl stickers. The works present a riotous assemblage of people and objects staring deadpan at the camera. Phrases such as I want to be strong like a tiger, and Think until you stink, are woven throughout the composition. These pieces encapsulate the chaos of digital media with their information overload, and contain winking reference to the dominant iconography of emoji. Similarly, Breuning’s black-and-white drawings of personified objects smooching or his wildly patterned animals have a Keith Haring-esque feeling of exuberance.

Screening in the second gallery is Breuning’s Life, a trilogy of videos which—due to the acoustics of the room—are nearly inaudible. However, streaming versions can be found via the artist’s website, where we can follow Breuning’s wide-eyed narrator as he bumbles through his world travels, garnering hugs and grimaces alike with his Pollyanna antics. Perhaps the comfort of one’s own home—or computer chair—provides a more accurate venue for Olaf’s entertaining YouTubian escapades.

Olaf Breuning runs June 13–July 30, 2015 at Michael Benevento(7578/ 7556 Sunset Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90046)

http://contemporaryartreview.la/olaf-breuning-at-michael-benevento/

Jessica Williams, Nowhere Girl No.2 (2015). Oil on linen. Image courtesy of the artist and Young Art.

Jessica Williams at Young Art

Young Art’s Hollywood storefront is blushing with florescent pink light: a jarring experience for those more accustomed to the pristine white-on-white-concrete-minimalism of most gallery experiences. Jessica Williams uses this unnatural lighting to illuminate her newest solo show Only Girl in the World, a room full of paintings that feels more secret club (of the after dark variety) than exhibition.

Imagery of flowers and fountains float around abstracted females, wallowing in their impressionistic, watery worlds on canvas. The works’ titles label the women depicted—Strip Mall Girls or Mirage Girls—without definitively describing them, adding an ambiguous mystique to the paintings. In the thick of it, one can’t help but think of Ophelia, the poster child for romantic female hysteria draped in blooms and tragically floating. However, in Williams’ hands these images also come with aWeetzie Bat taste of post-punk west coast fantasy. This sharpness along with Williams’ loose painterly technique keep the works from becoming too adolescent or melancholy, and instead leave the viewer with pictures rich with depth, feeling, and a bit of nightlife flair.

Only Girl In The World runs from May 9–June 6, 2015 at Young Art (5658 Hollywood Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90028).

http://contemporaryartreview.la/jessica-williams-at-young-art/